OSTEOPATHY

Osteopathy in the United States

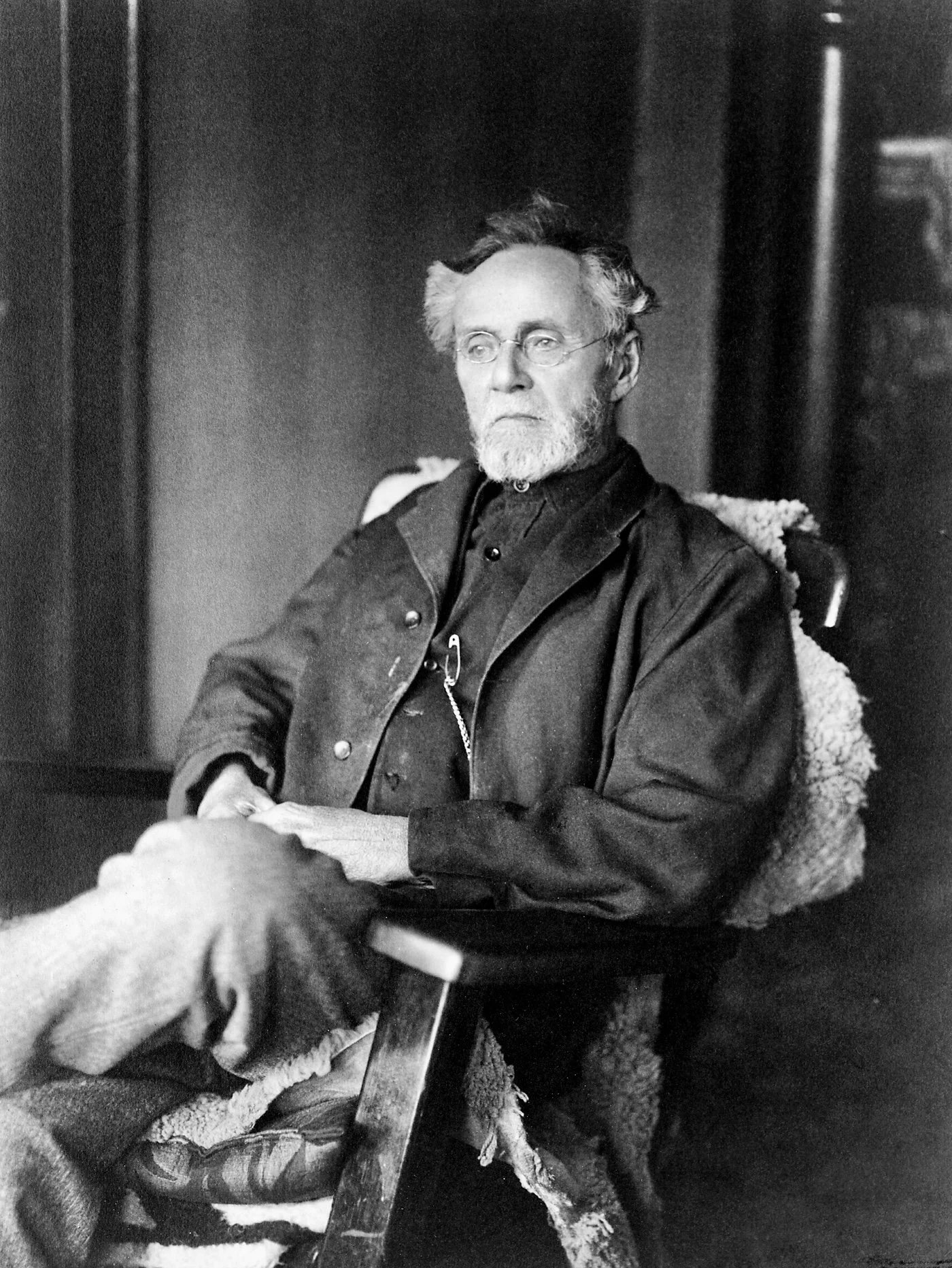

To understand the beginnings of osteopathy we need to look to the United States, to the time of the American Civil War, and to a tragedy that befell the family of a man named Andrew Taylor Still (Still, 1897, p. 98):

“It was in the spring of 1864; the distant thunders of the retreating war could be easily heard; but a new enemy appeared. War had been very merciful to me compared with this foe. War had left my family unharmed; but when the dark wings of spinal meningitis hovered over the land, it seemed to select my loved ones for its prey.

The doctors came and were faithful in their attendance. Day and night they nursed and cared for my sick, and administered their most trustworthy remedies, but all to no purpose. The loved ones sank lower and lower. The minister came and consoled us. Surely with the men of God to invoke divine aid, and men skilled in scientific research, my loved ones would be saved. Any one might hope that between prayers and pills the angel of death would be driven from our door. But he is a stubborn enemy, and when he has set his seal on a victim, prayers and pills will not avail.”

Still lost three members of his family to meningitis, two of his own children and one adopted child. He was a religious man and a medical practitioner, but these losses led him to question both his religious faith and his belief in medicine. He asked himself whether, when it came to sickness, God had left humanity guessing and whether medical doctors properly understood the causes of disease.

Through experience and reflection he came to believe that a loving and intelligent maker had deposited within each person remedies to cure infirmities, remedies which could be administered by “adjusting” the body. Skilled manipulation of the bony framework could bring about proper nervous communications and the proper circulation of blood and fluids, thereby assisting the body’s natural healing ability.

The word ‘osteopathy’ was derived from Greek words for ‘bone’ and ‘suffering’. Still recorded that the banner of osteopathy was “flung to the breeze” in 1874 (Still, 1897, p. 108), but the early history of osteopathy was almost certainly more complicated than his autobiography would have us believe. In 1875 Still advertised himself as a magnetic healer, rather than as an osteopath (Still, 1875). At that time another magnetic healer named Paul Caster was practising in Iowa and it is quite likely that Still was influenced by him (Waterman, 1914, p. 238). Later he described himself as the “lightning bonesetter” (Booth, 1905, p. 27). Before the introduction of medical licensure in the United States, he practised as a medical doctor, though evidence of his formal training in medicine has not come to light (Gevitz, 2014).

As licensure became a requirement for the practice of medicine in a growing number of states, Still was successful in applying for registration as a medical doctor. Even so, he considered osteopathy a distinct body of knowledge. He sought to teach osteopathy to others and was instrumental in the founding of the American School of Osteopathy in Kirksville, Missouri, in 1892. For a while persons who had previously studied medicine were not encouraged to apply to the School. The Journal of Osteopathy announced (1894):

“Experience has proven that those who have previously studied medicine, and afterwards tried Osteopathy, have been but a hindrance to the science. An allegiance to drugs once established, is almost impossible to overcome. After careful consideration, therefore, it has been established that as a general rule no person shall be admitted as a student who has previously studied and practiced medicine.”

So began an uncomfortable relationship between osteopathy and medical orthodoxy. Still was a medical doctor in name, but his system of healing was philosophically opposed to the mainstream medical culture of its day. It was in essence an alternative medicine. Be that as it may, following Still’s death in 1917, osteopathic writings did come increasingly to acknowledge a place for prescribed drugs in the care of patients (Miller, 1998). In time, as the number of osteopaths practising in the United States increased, osteopathy came to be legally recognized both in itself and as a parallel branch of medicine. This did not happen overnight and it did not happen without resistance. One of those who opposed the acceptance of osteopathy was Morris Fishbein, who was editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association between 1924 and 1950. He described osteopathy as a medical folly, in essence an attempt to enter the practice of medicine via the back door (Fishbein, 1925, pp. 58-59).

Osteopathy in Britain

By the beginning of the twentieth century word of osteopathy had reached Britain. John Martin and James Buchan Littlejohn, students of Still, both visited from the United States before the turn of the century (UK Passenger List, 1899a & 1899b). It was not long afterwards that the first American-trained osteopaths established practices in Britain (Collins, 2005, pp. 12-13; O’Brien, 2013, pp. 12-13). In due course they organized themselves, forming the British Osteopathic Society, which later became the British Osteopathic Association. Having taught osteopathy in the United States, John Martin Littlejohn, who was Glaswegian by birth, moved with his family to England where he worked to found an osteopathic school. The British School of Osteopathy was incorporated in 1917.

Osteopathy took a different path in Britain to the United States. In the United States osteopathy became analogous with the medical profession, but in Britain it did not. Whereas in the United States the legal basis for the profession of medicine was still being defined at the time of osteopathy’s emergence, in Britain legal boundaries already existed and osteopathy fell outside of these. In Britain the professional journey of osteopathy was therefore that of a separate occupation, rather than a branch of medical orthodoxy.

There were attempts to achieve statutory regulation for osteopathy in Britain during the 1920s and 1930s. These culminated in an examination of osteopathy by a Select Committee of the House of Lords in 1935, but its findings would not have made comfortable reading for osteopaths. The committee found osteopathy inadequately differentiated from other spheres of activity and insufficiently established in Britain to warrant regulation (House of Lords Select Committee, 1935, p. iv). Their report was disparaging of John Martin Littlejohn and of his running of the British School of Osteopathy, which was deemed to be “of negligible importance, inefficient for its purpose, and above all in thoroughly dishonest hands”.

A bill to regulate the practice of osteopathy was introduced to the House of Lords in 1936, only to be withdrawn. It would be more than fifty years before Parliament once again gave serious consideration to the statutory regulation of osteopathy. By that time osteopathy was more established and attitudes had changed. Crucially, osteopathy was presented not as an ‘alternative’ to medical orthodoxy, but as a ‘complementary’ system concerned with the biomechanics of the body (King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London, 1991, p. 10). This distinction was important for it represented an acknowledgment of orthodox medical authority. As Roberta Bivins has explained (2007, p. 38):

“Each position entails accepting a certain relationship with medical orthodoxy. If practitioners choose to regard their practices as ‘complementary’ to biomedicine, then they are accepting a more or less subordinate place within the orthodox hierarchy. The ‘complementary’ label accepts the universalizing claims of biomedicine; this has obvious implications in turn for the truth status of the ‘complementary’ system (particularly if it rests on another culture’s cosmology or body model). On the other hand, the label ‘alternative’ expresses an oppositional relationship between the system or practice to which it is applied, and biomedicine. Although this category resists incorporation and assimilation within biomedicine, and therefore escapes a lower status in the biomedical hierarchy of knowledge, it also hinders acceptance into the institutions of medical orthodoxy – the loci of most medical care in contemporary society.”

Political agitation and support from the medical profession resulted in the Osteopaths Act of 1993 (UK Parliament, 1993). The General Osteopathic Council was established to legally regulate osteopathic practice. The title ‘osteopath’ was protected under law, so that only those judged adequately qualified could use it.

References

Bivins R. (2007). Alternative Medicine? A History. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Booth E.R. (1905). History of Osteopathy and Twentieth Century Medical Practice. Press of Jennings and Graham, Cincinnati.

Collins M. (2005). Osteopathy in Britain: the First Hundred Years. BookSurge, Charleston.

Fishbein M. (1925). The Medical Follies. Boni and Liveright, New York.

Gevitz N. (2014). A degree of difference: the origins of osteopathy and first use of the “DO” designation. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 114 (1), 30-40.

House of Lords Select Committee (1935). Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords Appointed to Consider the Registration and Regulation of Osteopaths Bill. His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.

Journal of Osteopathy (1894). Requirements. Journal of Osteopathy 1 (1), 4.

King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London (1991). Report of a Working Party on Osteopathy. King’s Fund, London.

Miller K. (1998). The evolution of professional identity: the case of osteopathic medicine. Social Science and Medicine 47 (11), 1739-1748.

O’Brien J.C. (2013). Bonesetters: A History of Osteopathy in Britain. Anshan Ltd., Tunbridge Wells.

Still A.T. (1875). Advertisement. North Missouri Register 11th March 1875, p. 3.

Still A.T. (1897). Autobiography of Andrew T. Still. Published by the author, Kirksville, Missouri.

UK Parliament (1993). Osteopaths Act. 1993, Chapter 21, Elizabeth 2.

UK Passenger List (1899a). Incoming passenger list. Record for the Lucania, Liverpool, England, July 1899. Including the names of Elizabeth Littlejohn, John M. Littlejohn and Jas B. Littlejohn.

UK Passenger List (1899b). Outward passenger list. Record for the Campania, Liverpool, England, 26th August 1899. Including the names of J.M. Littlejohn, Jas B. Littlejohn and E. Littlejohn.

Waterman H.L. [editor] (1914). History of Wapello County, Iowa. Volume 1. The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago.