BONE-SETTING

Bone-setting in Britain

In England, Ireland and Wales the dissolution of the monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII brought to an end a way a life which for many had centred on religious communities. The place of Catholic monasteries in caring for the sick became for the most part a thing of the past. Hospitals with links to the Catholic Church were closed, to be replaced by remodelled civic institutions where medicine was practised and taught, but their capacity to provide for the needs of the public was incomplete. From the time of the Renaissance the term ‘bone-setter’ was used in written English to describe folk practitioners who engaged in the treatment of fractures, dislocations and other musculoskeletal conditions using manipulation. Lacking in formal training, the knowledge and skills of bone-setters were passed on through oral tradition, often within families.

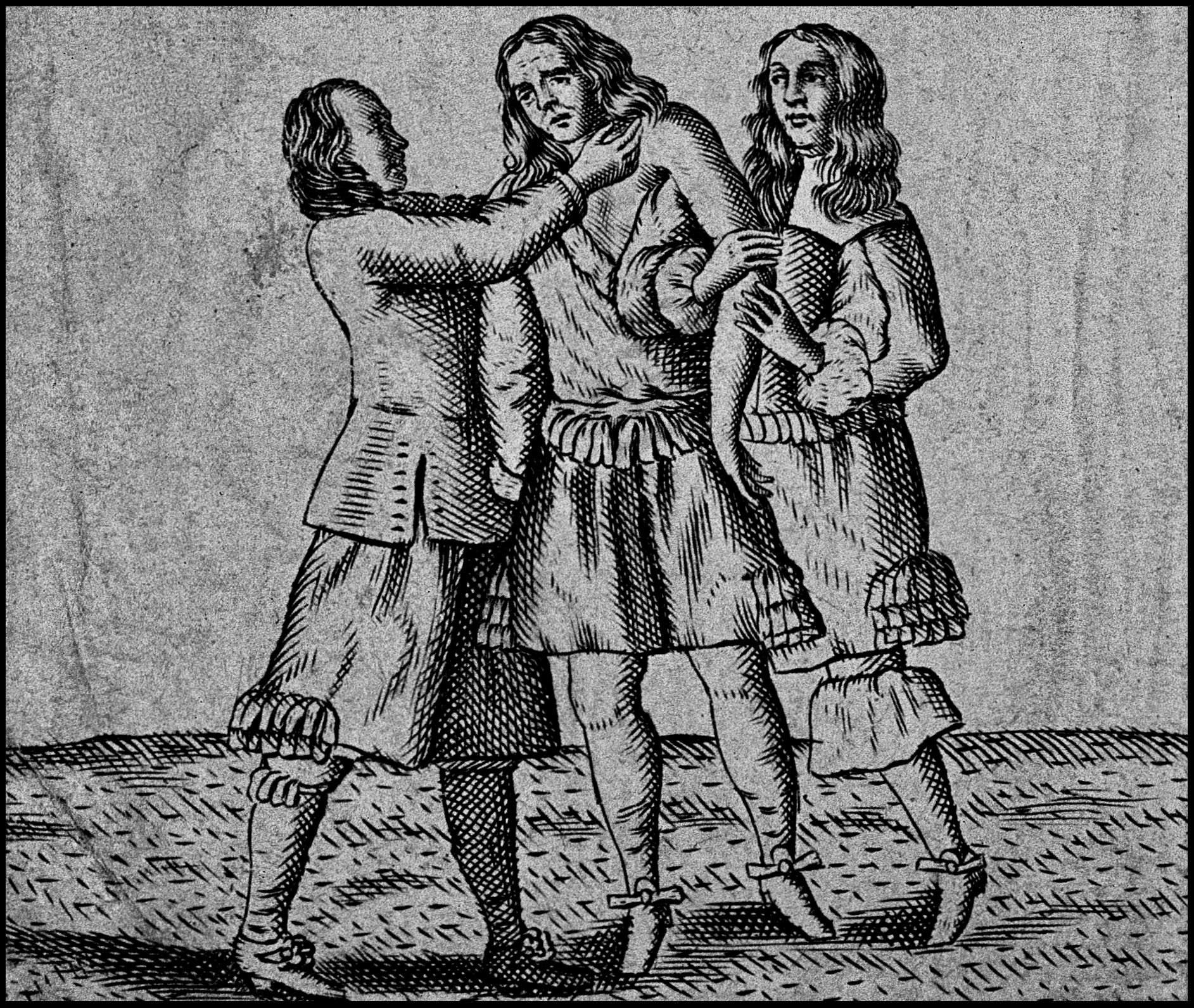

The nature of bone-setting was such that little was written about it by its practitioners, but some texts do exist. The Compleat Bone-Setter, ostensibly by Friar Thomas Moulton, but revised and translated by Robert Turner, was published in English in 1656, with a second edition issued nine years later (Turner, 1665). According to the preface it was written so that every man, learned or leud, rich or poor, could come to be their own physician in time of need. It prescribed remedies for a variety of conditions, including broken bones and dislocated joints.

Typically bone-setters were ordinary people who were seen to have a gift for dealing with injuries by those in their community. The idea that such people provided a useful service was contested by some, including Richard Wiseman, surgeon to King Charles II. He wrote of (Wiseman, 1676, p. 478):

“the inconvenience many people have fallen into through the wickedness of those who pretend to reducing luxated joints by the peculiar name of bone-setters: who (that they may not want employment) do usually represent every bone dislocated they are called to look upon; though possibly it be but a ganglion, or other crude tumour or preternatural protuberance of some part of a joint.”

Most bone-setters did not become well-known, but there were exceptions. Sarah Mapp was one, a woman memorialized by the London press. In 1736 she was the subject of the following verses of a comedy performed at the Theatre Royal, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London (Gentleman’s Magazine, 1736, p. 618):

“You surgeons of London who puzzle your pates, to ride in your coaches and purchase estates, give over for shame, for your pride has a fall, the doctress of Epsom has outdone you all.

What signifies learning or going to school, when a woman can do without learning a rule, what puts you to nonplus and baffles your art, for petticoat practice has now got the start.

Dame nature has given her a doctor’s degree, she gets all the patients and pockets the fee, so if you don’t instantly prove her a cheat, she’ll loll in her chariot whilst you walk the street.”

The contribution of bone-setters was perhaps most appreciated in communities that were not centres of medical learning. Bone-setters often plied their trade in places where academic medicine was less influential and where there was the most need. In rural communities, and when Britain came to industrialize, in industrial communities, bone-setters provided care for workers and for others who could not afford the attentions of ‘educated’ doctors. The epitaph of Benjamin Taylor, who was buried at Watermillock, in what today is the English Lake District, read as follows:

“Benjamin. Who was an eminent and successful bonesetter, equalled by few, not perhaps surpassed by any in his time. Having exemplified in his practice the art of replacing broken and dislocated bones in every part of the human body. His benevolent disposition to the unfortunate poor particularly endeared him to patients of that description. He lived at Stainton in the parish of Dacre and died universally lamented on the 4th day of Jan. 1808 in the 62nd year of his age.” (Inscription from a headstone at All Saints’ Church, Watermillock, Cumbria)

Bone-setting in international context

In Spain, during the Renaissance and afterwards, the word ‘algebrista’ was used to describe a bone-setter. The French equivalent was ‘renoüeur’, which meant to tie again or re-join (Oudin, 1607; Boyer, 1699). Another French word for bone-setter was ‘Bailleul’, which was actually a family name. Jean de Bailleul was Abbot of Joyenval and almoner to King Henry II (Scévole de Sainte-Marthe, 1630, p. 155). It seems that he and members of his family were so well known for their skill at bone-setting that the Bailleul name came to be used to describe bone-setters more generally.

As Europeans colonized other parts of the world, explorers and settlers came across indigenous peoples who practised manual therapies. While visiting the Pacific island of Tahiti in 1777, James Cook informs us that he received a physical treatment called ‘romee’ from a group of local women (Cook, 1784, pp. 63-64). In North America, European settlers encountered the healing practices of the native American peoples. It has been argued that these native healing traditions may have informed the subsequent development of osteopathy (Zegarra-Parodi et al., 2019). In this regard it is important to recognize the interplay that would have existed. There can be little doubt that the settlers would have been influenced by the practices of indigenous peoples, but they also brought with them practices founded in European traditions. According to Hazard (1879), James Sweet came to America from Wales in 1630 and settled in North Kingstown, Rhode Island. His family came to be known for their “natural gift” in setting dislocated and broken bones.

References

Boyer A. (1699). The Royal Dictionary. Part I. In English and French. R. Clavel et al., London.

Cook J. (1784). A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean Undertaken by the Command of His Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere. To Determine the Position and Extent of the West Side of North America; its Distance from Asia; and the Practicality of a Northern Passage to Europe. Volume II. Printed by W. and A. Strahan, for G. Nicol, & T. Cadell, London.

Gentleman’s Magazine (1736). Gentleman’s Magazine. Volume VI.

Hazard T.R. (1879). Recollections of Olden Times: Rowland Robinson of Narragansett and his Unfortunate Daughter. With Genealogies of the Robinson, Hazard, and Sweet Families of Rhode Island. John P. Sanborn, Newport.

Oudin C. (1607). Tesoro de las dos Lenguas Francesa y Española. In French and Spanish. Marc Orry, Paris.

Scévole de Sainte-Marthe (1630). Gallorum Doctrina Illustrium, qui nostra Patrumque Memoria Floruerunt, Elogia. In Latin. Jacob Villery, Paris.

Turner R. [editor and translator] (1665). The Compleat Bone-Setter Enlarged: Being the Method of Curing Broken Bones, Dislocated Joynts, and Ruptures, Commonly Called Broken Bellies. Second Edition. Ostensibly by T. Moulton. Translated, revised and enlarged by R. Turner. Also included: The Perfect Oculist, The Mirror of Health and The Judgement of Urines. Printed for Thomas Rooks, London.

Wiseman R. (1676). Severall Chirurgicall Treatises. Printed by E. Flesher and J. Macock, for R. Royston and B. Took, London.

Zegarra-Parodi R., Draper-Rodi J., Haxton J. and Cerritelli F. (2019). The native American heritage of the body-mind-spirit paradigm in osteopathic principles and practices. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 33-34, 31-37.