MEDIEVAL PRACTICES

Manipulation in medieval Europe

By 500 CE the Roman Empire was no more. With its decline came cultural change. In the West there was political division and a blending of Greco-Roman and Germanic traditions. In the East the Roman Empire became the Byzantine Empire with its capital at Constantinople.

European medicine came to be influenced by Christianity. Christian teachers promoted the idea that spiritual wellbeing was more important than physical wellbeing and that disease was a product of sin. Those who practised medicine, who laid hands on patients, or performed manipulation without sanction of the Church were prone to criticism. In the sixth century Gregory, Bishop of Tours, who was later canonized by the Catholic Church, was disparaging of the treatment provided by a man whose name was Desiderius (Brehaut, 1916, pp. 205-206):

“There was in that year in the city of Tours a man named Desiderius who claimed to be great and said he could do many miracles. He boasted too that messengers were kept busy going to and fro between him and the apostles Peter and Paul. And as I was not at home, the common folk thronged to him bringing the blind and lame but he did not attempt to cure them by holiness but to fool them with the delusion of necromancy. For he ordered paralytics and other cripples to be vigorously stretched … his attendants would lay hold of a man's hands and others his feet, and pull in opposite directions so that one would think their sinews would be broken, and when they were not cured they would be sent off half-dead … his trickery was exposed and stopped by our people and he was cast out from the territory of the city.” (English translation by E. Brehaut)

Although we cannot know for certain, the stretching employed by the attendants of Desiderius may well have been based on Hippocratic methods. If so, then Gregory’s denunciation of Desiderius might be seen as a rejection of Hippocratic practices, but it seems more likely that the issue of religious authority was paramount. Desiderius was seen as a pretender to the authority of the Church.

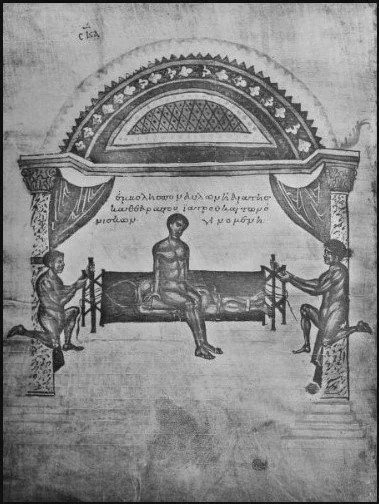

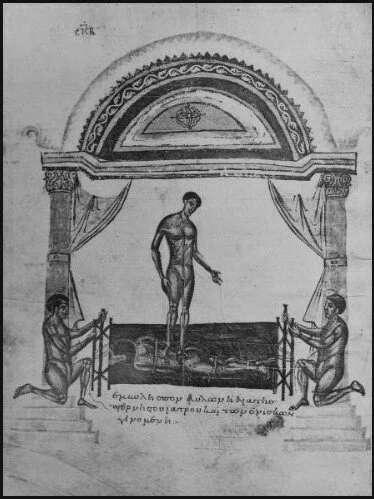

From the time before the printing press and before widespread use of paper, a time in which levels of literacy were low, relatively little information about the use of manipulative therapy has come down to us. Even so, we do know that Greco-Roman techniques survived. Images of Hippocratic methods appeared within the Nicetas Codex, an illustrated manuscript produced in Constantinople in or about 900 CE (Nicetas, circa 900 CE, pp. 182-223).

During the medieval period European monasteries and hospitals run by the religious were places of healing, both spiritual and physical, however during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries canon law discouraged ‘regular’ members of the Catholic clergy, those who were subject to a ‘rule’ of life, such as that of St. Benedict, from studying medicine in order that they concentrate their attention on spiritual matters (Amundsen, 1978). This left the way open for others to develop medical and surgical skills. Today there is a tendency to associate the practice of surgery with incision, but as the Dominican friar and bishop of Cervia Theodoric Borgognoni explained in his thirteenth century Chirurgia, the word surgery derived from the Greek ‘cheiros’ meaning hand and ‘ourgia’ meaning action (Campbell and Colton, 1955, p. XV; see also pp. 4-5). It included both the management of wounds and the treatment of fractures and dislocations by means of manipulation.

Manipulation and Arabic culture

Beyond Europe, as Arabic civilizations developed in the Middle East from the seventh century CE Greco-Roman manuscripts were acquired and translated by Muslim scholars. The Persian polymath Ibn Sina (circa 980-1037 CE) produced a five volume encyclopaedia of medicine in which was described manipulation inspired by Greco-Roman methods (Nassar, 2007, Book IV). Today in English we use the word ‘algebra’ to refer to a branch of mathematics. In fact the word ‘algebra’ comes from the Arabic term ‘al-jabr’ which referred not only to the branch of mathematics, but also in medical lexicon to the restoration of bony parts in cases of fracture or dislocation (Oxford English Dictionary, 2021).

During the crusades of the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when Western Europeans attempted to take lands which were under Islamic rule, Christian and Muslim scholars came to know of one another and ideas were exchanged. Arabic medicine influenced European medicine. Ancient texts which had been translated into Arabic, were translated once again, this time into Latin. Methods of joint manipulation were a part of the corpus of Islamic medical knowledge.

References

Amundsen D.W. (1978). Medieval canon law on medical and surgical practice by the clergy. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 52 (1), 22-44.

Brehaut E. [translator] (1916). History of the Franks by Gregory Bishop of Tours. English translation by E. Brehaut. Columbia University Press, New York.

Campbell E. and Colton J. [translators] (1955). The Surgery of Theodoric. Volume I (books I and II). Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., New York.

Jacob de Burgofraco [printer] (1510). Primus Avicennae Canon. Latin translation of Book I of Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine. Jacob de Burgofraco, Pavia.

Nassar K.T. [translator] (2007). Kitab al Qanoun fi Al Toubb. 1593 version of Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine, originally published by In Typographia Medicea, Rome. In Arabic with English translation of contents. Saab Medical Library, Beirut.

Nicetas (circa 900 CE). Nicetas Codex. In Greek. [Laurentian Library, Florence]

Oxford English Dictionary (2021). Algebra. Oxford English Dictionary (Third edition). Modified online version. December 2021. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Schöne H. (1896). Apollonius von Kitium. In German. Druck und Verlag von B.G. Teubner, Leipzig.