MEANINGS

History as subjective

“The facts of history never come to us ‘pure’, since they do not and cannot exist in a pure form: they are always refracted through the mind of the recorder. It follows that when we take up a work of history, our first concern should be not with the facts which it contains but with the historian who wrote it.” (Carr, 1961, p. 24)

History is concerned with study of the past. It is about people and their actions. It involves not only the examination of documents, but also of other sources of evidence such as objects, photographs and oral testimonies. Rarely is history objective. Instead historians interpret the past. Although academics generally do their best to present history as it actually was, in searching for meaning and in explaining the past a degree of subjectivity can be inevitable. Historians are a part of their research. They are not separate from it.

Historians have conceptions and biases which influence their work. The author of this study is no exception. His writings emphasize the country of his birth and his native language, which is English. He is a chiropractor, a practitioner of joint manipulation. As such, he is positively disposed towards the practice of joint manipulation. He is opposed to unwarranted tribalism in health care and is a supporter of interprofessional collaboration. He believes in evidence-based health care, which involves the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values. He sees joint manipulation as offering value in the management of musculoskeletal conditions, but thinks that it should be used selectively and normally as part of a multimodal approach to care.

Medicine: inclusive and exclusive meanings

The history of joint manipulation forms a part of the history of medicine and definitions of medicine are relevant to its understanding. As a practice medicine is concerned with the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and with experts who carry out these functions. Considered in a narrow sense medicine focuses on the work of physicians, which is to say those doctors most strongly linked to the prescription of medicines. More broadly, medicine is often taken to include surgery. In Britain and in other countries physicians and surgeons study together at undergraduate level and after graduation are regulated in unison under law. Today, with respect to the care of humans (for there is also veterinary medicine), there is a tendency to associate medicine with members of the medical profession, which in Britain refers to those practitioners who are regulated by the General Medical Council.

This was not always the case. Before the Medical Act of 1858 (UK Parliament, 1858), in the absence of legal definition, it was not always clear who was and who was not a medical doctor. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was considerable diversity in medical practice with ‘regulars’ and ‘irregulars’ working in a climate of medical pluralism (Harris, 2004, p. 92; Loudon, 1986, p. 13). The definition of medicine could therefore reasonably include orthodox and heterodox practices of various kinds. As medicine professionalized in the years leading up to the Medical Act the distinction between orthodox and heterodox practice became more apparent, while the social distance between physicians and surgeons decreased. In a lecture reported in the Lancet in 1826 the surgeon William Lawrence advised his fellows that they must “be contented to use the word medicine, although it is equivocal, being frequently employed in contradistinction to surgery” (Lawrence, 1826).

Today, although the word medicine is used to describe the regulated profession, it is still often applied in a wider, more inclusive manner. In this context dentistry can be considered a branch of medicine and chiropractic medicine is not a misnomer.

Meanings of manipulation

Definitions of medicine highlight the complexity of language, of words which are in everyday use and which for the most part we take for granted without further reflection. Like medicine, the meanings of ‘manipulation’ are multiple (Oxford English Dictionary, 2022). The word was used in the eighteenth century to describe both a method of digging for silver ore and the handling of apparatus and reagents in chemical experiments. These are archaic uses. More recently the term has been applied to handling more generally, to the subtle, skilful and devious control of people, and in human and veterinary medicine to actions involving movement of parts of the body, especially its articulations.

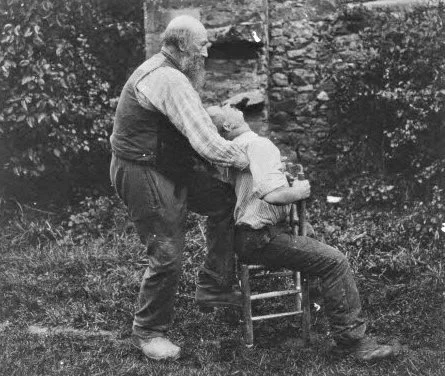

Joint manipulation is both an examination procedure and a treatment. Even in the context of treatment it is an expression that means different things to different people. Joint manipulation is generally done by hand, but it can involve the use of other body parts, or be instrument-assisted. It is a passive procedure applied by the practitioner to the patient, except where active participation of the patient is required. It involves a high velocity, low amplitude thrust, but can also describe a variety of mobilization techniques of varying speed and amplitude. Its aim is to restore normal joint movement and function, but it is also utilized to realign and establish optimal joint position. Joint manipulation is used in the promotion of musculoskeletal health, but there are those who see value in its application for organic disease. It is both an ancient and modern practice, a form of alternative medicine and a constituent of medical orthodoxy.

A broad description of joint manipulation might encompass all of the above, but narrower definitions have also been proposed. In 1962, in a presentation to the Physiotherapists’ Society of South Australia, Geoffrey Maitland reflected upon approaches to joint manipulation as a therapy and drew a distinction between those procedures that involved a “forcible thrust” and those that did not (Maitland, 1963). The latter he suggested should be termed mobilization rather than manipulation. In the preface to the first edition of his book Vertebral Manipulation, he wrote (Maitland, 1964, p. vii):

“There are two ways of manipulating the conscious patient. The first, better thought of as mobilization, is the gentler coaxing of a movement by passive rhythmical oscillations performed within or at the limit of the range: the second is the forcing of a movement from the limit of the range by a sudden thrust.”

Maitland described four grades of mobilization and one of manipulation, a classification which came to be widely used in the teaching of physiotherapy.

The word ‘adjustment’ has been used as a synonym for manipulation by some practitioners. For others the word adjustment has been preferred in describing their techniques. Bartlett Palmer, the son of chiropractic’s founder, wrote (Palmer, 1920, pp. 87-88):

“A Chiropractor is a hand practitioner; he adjusts displaced parts, he repairs a disordered human machine, he puts in order and sets to right the displaced bones of the skeletal frame which are not in their proper position … We do not manipulate; the masseur, magnetic and the Osteopath do. We repair the human machine by adjusting.”

It is worthy of note that Andrew Still, the founder of osteopathy, had previously advised that if in pain one should “let a skilful engineer adjust your human machine, so that every part works in accordance with nature's requirements”, that engineer being an osteopath (Still, 1897, p. 289).

References

Carr E.H. (1961). What is History? Vintage Books, New York.

Harris B. (2004). The Origins of the British Welfare State: Social Welfare in England and Wales, 1800-1945. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Lawrence W. (1826). The introductory lecture to a course of surgery. Lancet 11 (162), 1-9.

Loudon I. (1986). Medical Care and the General Practitioner, 1750-1850. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Maitland G.D. (1963). The problems of teaching vertebral manipulations. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 9 (3), 79-81.

Maitland G.D. (1964). Vertebral Manipulation. Butterworths, London.

Oxford English Dictionary (2022). Manipulation. Oxford English Dictionary (Third edition). Modified online version. March 2022. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Palmer B.J. (1920). The Science of Chiropractic. Its Principles and Philosophies (Fourth edition). The Palmer School of Chiropractic, Davenport.

Still A.T. (1897). Autobiography of Andrew T. Still. Published by the author, Kirksville.

UK Parliament (1858). Medical Act. An Act to Regulate the Qualifications of Practitioners in Medicine and Surgery. 1858, Chapter 90, Victoria.